Iran wants its monarchy back

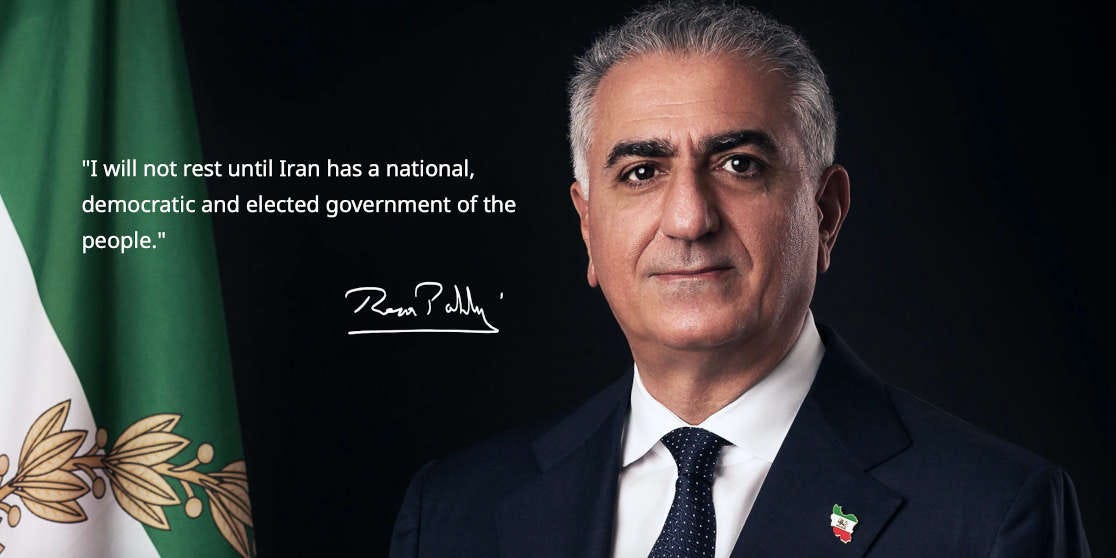

There are protests in Iran again. But this time, something is different. In the uprisings of 2019, 2022 and 2023, the dominant slogan was negative: what Iranians did not want. ‘Death to the dictator’ echoed through the streets. Today, the country has moved beyond rejection. Now there is affirmation. A name is being chanted: Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi.

More than ten Iranian cities have risen up in recent days, from the most conservative quarters of society to elite universities. Across Iranian cities one hears slogans: ‘Pahlavi will return’, ‘Javid Shah’ – the Persian equivalent of ‘Long live the King’ – and simply, ‘King Reza Pahlavi’. For the first time since the revolution, Iranians are not merely denouncing a regime; they are articulating an alternative.

What does the renewed popularity of the Pahlavi name signify? Some context is helfpul. Last year, the Crown Prince, the son of Iran’s last Shah visited Britain, where he met Boris Johnson, David Cameron and Nigel Farage. In 2023, he travelled to Israel and met Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. This is a remarkable vibe change for a country whose ruling ideology is premised on the destruction of Israel and names the street on which the British embassy is based Bobby Sands Street, after the IRA hunger-striker who died in a Northern Irish prison in the 1980s.

Iranians are once again resisting what Scruton called ‘the tyranny of evil mullahs’

The message Iranians are sending is disarmingly simple: we want to return to normality. They want an end to the madness imposed by an Islamic dictatorship that has isolated Iran from the world and from itself. Normality means peaceful relations abroad and civic peace at home. It means an Iran that does not define itself through permanent revolution.

The Islamic Republic has, from its inception, defined itself against the West – from the seizure of the US embassy in 1979 to the routine arrest of British nationals simply for being British. This is not incidental excess; it is ideological design.

The regime’s propaganda machine insists on reducing the current unrest to economics. Inflation, it is true, has devastated Iran. Forty-five years ago, one US dollar was worth seven tomans. Today it exceeds 145,000 – and can fluctuate by as much as 25 per cent in a single day. A devaluation like the 1992-pound crisis is just a normal day in Iran’s economy.

But this explanation collapses under scrutiny. The protests did not originate in universities or among radical students, but in the bazaar – the most conservative segment of Iranian society. Shopkeepers, traders, ordinary businesses. When the bazaar chants ‘God Save the King’, this is not an economic protest. It is a profoundly political one. When the most conservative strata of society demand regime change, the regime’s legitimacy has collapsed and can’t be fixed with economic policy.

To understand how Iran arrived here, one must recall what was lost. The images of pre-revolutionary Iran, cosmopolitan, confident, recognisably Western, now look almost unreal. How did a country move from that world to one that inspired The Handmaid’s Tale?

The answer lies in what the late Shah described as ‘the unholy alliance of Islamists and the Left’. In the years leading up to the 1979 revolution, these two forces converged in their hatred of liberal modernity. Among their most influential Western cheerleaders was the French historian and philospher Michel Foucault, who travelled to Iran and famously hailed the Islamic Revolution as a source of hope in a hopeless world.

But one may ask the most cited social scientist in history, Mr. Foucault: didn’t the religious character of the movement bother you? Apparently not. Foucault dismissed such concerns by citing Marx: religion, he argued, was ‘the spirit of a world without spirit’. Islam, for him, was merely a vehicle for anti-imperialist resistance. Foucault visited Iran with his boyfriend before the revolution. He could not return after the revolution he supported succeeded – for reasons that should be obvious. Just as ‘Gays for Palestine’ cannot go to Palestine.

While post-modern intellectuals failed spectacularly to understand what was unfolding, one writer did. He, too, wrote for The Spectator: Sir Roger Scruton. In his 1984 essay for the Times, ‘In Memory of Iran’, Scruton begins with a question that still haunts whoever reads it: ‘Who remembers Iran?’ He asks what became of the activists, journalists and intellectuals who demanded the Shah’s downfall – and what they forgot: the Shah’s achievements:

His successes in combating illiteracy, backwardness and powerlessness, his enlightened economic policy, the reforms which might have saved his people from the tyranny of evil mullahs, had he been given the chance to accomplish them.

Today, Iranians are once again resisting what Scruton called ‘the tyranny of evil mullahs’. But this time, the difference is decisive. Iranians know what they want – and they want the monarchy back.

For the first time, I am hopeful. Not because of Western media narratives, but because Iranians themselves are finally disillusioned with reform from within a system designed to resist reform. They are saying openly what was once unthinkable. They do not want an Iranian Deng Xiaoping. They want a General de Gaulle.

Is this the endgame? As a pessimist – especially after seeing all the hopes that died in the protests of 2019, 2022, and 2023 – I am surprised at my hopefulness this time. One thing makes me hopeful: figures like Netanyahu in Israel and Trump in the White House, who, like Iranians themselves, are disillusioned with the so-called reformers. As Shakespeare wrote, ‘Diseases desperate grown, by desperate appliance are relieved, or not at all.’ The Islamic Republic is a desperate disease. It can’t be reformed; as Henry Kissinger understood really well, ‘An Iranian moderate is one who has run out of ammunition.’

Written by Mani Basharzad